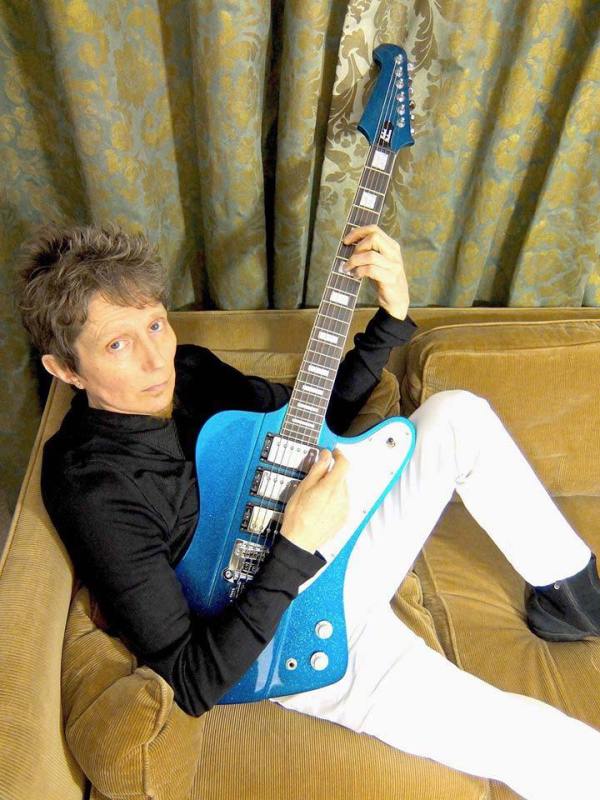

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of speaking with this bass legend – a man who at 73 years young refuses to show any signs of slowing down the pace. I don’t need to get into specifics regarding who Jack has played with or what he has accomplished, because the list goes on for eternity. I will say this, though; if ever there is a time for younger aspiring bass players to seek out musical royalty, they must do it now, and go see Hot Tuna perform this summer as part of the “Wheels of Soul” tour with Tedeschi Trucks Band and The Wood Brothers. Trust me, from personal experience, you will not be disappointed!

For now, I hope you enjoy my in-depth conversation with Jack, spanning over fifty years’ worth of lifetime achievements and milestones:

JB: Last December, I had the opportunity to see Hot Tuna perform live for the first time ever in Fairfield, CT. I wish to congratulate you and Jorma Kaukonen for sustaining such a long musical partnership within the “American blues roots rock” community. Is it true it’s been almost five decades that you two have been playing together?

JC: Well, we started in high school in 1958. We had a little high school band together when I was 14 and he was 17. Then, he graduated and went off to Antioch College, which is where he started learning his finger-picking style. We hooked back up again at the beginning of Jefferson Airplane. I joined a few months after Jefferson Airplane was put together – in 1965 – and then I did my twenty years out in San Francisco.

JB: That is going to lead into my next question. Having this friendship/partnership for so long, are you still learning from one another, and what is the key ingredient that has made the band last for this amount of time?

JC: I don’t think we look at it as a band, as such, but essentially, Jorma and I have grown up listening to various styles – like folk, blues and the Americana genre, as well as many others. I think we realized that the gift we have requires pursuing it. It is not enough just being proficient at playing; you need to pursue that gift with all curiosity, as well as keep your standards up to a level where you want it all to be as honest as possible. So, if you do that, then you require that from each other, and that is a fun thing. This is not a chore; this is a healthy thing, and so in the musical world, we try to do that. In the personal world, we see ourselves outside the musical confines, so that we see each other as friends and human beings who are able to do this and do it well – but also appreciate how lucky we are to be able to do it.

That being said, we work very hard at it. This allows us to make sure that there aren’t any roadblocks getting in the way of our musical business. Quite often, bands come together for the business, putting up the band as a musical entity or structure. I think that it helps tremendously that Jorma and I have references that are not connected to the band or the music or the partnership that we do as Hot Tuna … and so if the elements of life and all of the distractions that come along in life get to be intrusive, we are fortunate enough to step back and say, “Listen, you know, I remember your mom coming and making a roast beef sandwich.” He wouldn’t remember that, but I remember visiting his parents and grandparents as kids before we knew that we were really going to do this for our whole lives, and I think that makes a big difference in keeping our perspective.

JB: Right, you established that friendship first off, before moving on as a musical duo.

JC: Yes, but a friendship – like any kind of a relationship – requires work as you get older and gain maturity and things change in your life, so it is something that always has to be worked at.

JB: Have you ever felt performing live that there have been moments (because you have this innate synergy) you ventured into stretching out or extending a tune? Have you ever had an instance where Jorma is going one place and you follow him seeing where you end up meeting each other in the middle?

JC: We do, indeed, do that with each other. I think that is what makes us hold interest with each other, and we allow one another to do that freely. So if I pull something out in one direction, you peep over that wall and see what’s on the other side.

JB: That is what I was going to comment about in your bass playing. I have noticed when watching you perform that there is this sensibility of swing, and there was no noodling around the fret board. Has it been a conscious decision to make your bass lines more melodic, where each note being played really has a purpose?

JC: Absolutely, absolutely… I get that from a lot of my early jazz listening. When I started playing guitar at age twelve, my father belonged to the American Jazz Society. He was a professional dentist in Washington, but he was an audiophile, and I always liked the small combo stuff, such as Bix Beiderbecke and Eddie Condon, and even the small New Orleans band combos that would play in and around one another. I liked in the individual players Jelly Roll Morton, and loved the the way that his left and right hands would move and interchange within each other … that is where I got a lot of my sensibility about what the bass can do. I love orchestral works, where you listen to the bass violas go up through the cello range and the music flows through the low end up to the midrange and upper midrange. I go for that in playing my music, I love the melody aspect, but it always has to swing.

JB: Yes, I can hear that.

JC: I am so glad that you used the term “swing,” because people don’t use it much, anymore. Even though you’re playing the melody, it’s not just about how intricate you can make the combination of notes as you search for creative stuff to play. For me, it is more about keeping the “seductive” aspect of the playing – which is the swing within – that to make those melodic notes mean something. Whatever guitar style Jorma is using – which is primarily a thumb and two fingers and finger-picking style – what is unique about he and I playing together like that is our style; that is complete music, in and of itself. It is like two hands on the piano, so he can sit and play the guitar with the thumb moving back and forth between contrapuntal lines and groove rhythm lines – as well as the chords and melody interspersed – but they are not just whole chords being thrashed across the guitar or playing lead lines, like in a linear guitar approach. That frees me up to work within the melodic world, and the bottom does not drop out of the music. Now, I can’t do that with every other player. I figure if I am playing with somebody who is playing either a melody with a flat pick or is playing rhythm, then quite often, that requires more pattern-oriented playing in order to have the support there. You shift your playing around to suit the needs necessary. Doing what Jorma and I do as Hot Tuna, the way he plays allows me to do much more. My goal is always to intertwine with that, so if I am moving up the neck and playing a little more melody, it has to reach a point and a culmination, so I drop back down to the low end to pick up from that departure point to center it back in. Even when I am doing the melodies or moving around in there, they have to hook in with the rhythm going on, and hopefully the goal is not for it to be a distraction, but to just be another level within the music.

JB: Would you say that when going into the lower register, are you more cognizant of the kick drum and paying closer attention to the drummer?

JC: Well yeah, absolutely. I am always paying attention, because when we’re doing electric Hot Tuna, that is what you do. When I’m doing acoustic Hot Tuna, the lack of a drummer is a strength unto itself, because your playing has to be spot-on and in a manner where that groove does not go away. Now, you don’t have to have someone stating where 2 and 4 is all the time, but when you have a drummer, yes, there is another dynamic of which to work within the bass drum. It’s not just about keeping time, it’s about working within that rhythmic format of the bass, drums, guitar combo to get that rhythmic structure.

JB: Do you have a preference as far as going out acoustically or electric, or do you enjoy both equally?

JC: It’s like driving a different kind of car. You get into that car, whether or not you’ve got a jeep grand Cherokee or whether you’ve got a Ferrari – which I don’t have.

JB: Nor do I! [both chuckle]

JC: But you know, there are different elements, and you work within those elements, and I honestly love them both. Lately, we’ve been playing as the electric Hot Tuna, which is a very odd form. There is a lot of ground to cover when you’re working with a trio like that; it’s a lot of fun. As soon as you add other people and turn it into a quartet, then you move into a more functional background. Everybody does, because there is less room to work within, so each format has different structural aspects that are best to adhere to.

JB: Is there a particular drummer over the years who has kept you on your toes rhythmically, and was it a challenge that really opened you up more as a bass player/musician?

JC: That is an interesting question. They all do, without singling out a particular, and I’ll tell you why. Because whatever your preference is, it’s not like you can always pick or choose who to play with. I don’t require another drummer to fit necessarily into my format, I listen to how they play, they listen to how I play, and we work out a new team dynamic. It’s kind of like if you have a football team or soccer team and you have different players, you work around the dynamics and talent that is presented. You may be initially frustrated that perhaps you can’t get to a place you did with another player, but it needs to be dropped and you’ve got to investigate what you have in front of you. I think if you do that, then you don’t tend to look at the epitome of who did this or who did that. I can name some drummers who knocked my socks off that I have played with. They’ve all had something going on, and sometimes I don’t even realize it as much while it’s going on as later on, in retrospect. I will sometimes say, “Wow, we really did that well,” because you know, when you’re younger, you’re pushing all the time, and you’re not really satisfied too much with what you’ve done. I think as you get older, as well, I’m not really satisfied with what I’ve done. It’s really about the night that you’re playing … that night. You try to duplicate what you did the night before, and of course you never do. It is of course futile to do that, and it’s not healthy.

JB: Let’s talk about you recording with Jimi Hendrix, because I know that you sat in on the Voodoo Chile jam session with Jimi, Steve Winwood and Mitch Mitchell.

JC: Yeah, right, and that wasn’t a jam session. I mean, he said, “Let’s play a slow blues,” and we in today’s terms “jammed” and improvised. That was a long number for those days in timing length. Having a 15-minute song getting on an album was practically unheard of, except in the jazz world.

JB: Right. How did that whole session evolve?

JC: I think it was 1968. Jefferson Airplane was on tour, we were in New York doing the Dick Cavett show. I had known Jimi from coming out to the Fillmore and playing on the west coast, and there was his drummer who I got friendly with and really admired – Mitch Mitchell – and he and I had jammed a few times together while Jimi was playing at the Fillmore. We played the Fillmore all the time and had a rehearsal hall next door, and Bill Graham was our manager at the time, too. We had played a few times together, but really admired one another’s playing. While taping the Cavett show earlier in the evening, I went over to hear Traffic, which was the name of Steve Winwood’s band. I think it was their first American tour, actually. Jimi had known Steve Winwood and those guys in Traffic from working in England and putting together his band, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, so we went over to hear them after we did the Cavett show. Jimi walked in and said, “Hey, listen. I’m recording my new album. Would you guys all come over after the show?” We watched him record the good part of the evening. We all crammed in there – probably about 15 of us, including Jorma and I. Don’t forget, it was 2:00am in the morning, and at around 6:30am or something like that, he finished doing his work and said, “Let’s play the blues,” and he reworked Voodoo Chile into a long slow format. He showed us the changes in it, we ran it down one half a time and he broke a string and put another string on and did the full session. Then, we left at about 7:30 in the morning, because we had to be in DC. Jefferson Airplane piled into our Ford LTD wagons and headed down to DC to do another show. A month later, out in San Francisco at our offices at 2400 Fulton St., I get a phone call from Jimi. He said “Listen, would you mind if I put that track on the album?” I said, “I don’t mind, that would be great,” and that’s how it happened.

JB: That’s truly amazing. What happened to Noel Redding? Where was he during this session?

JC: He was in the vocal booth staring at me through the glass.

JB: So Noel knew that he would not be playing on this track?

JC: No, no it was okay – it was a jam. They didn’t know it was going to be a double album, I don’t think. In any case, it was a freer kind of time. Jimi had broken away from his producer Chaz Chandler and was producing it on his own, so part of the things he wanted was to get more freedom in the studio. A lot of the bands were doing it. We were doing it we did it with After Bathing at Baxters, our third album. We spent much more time in the studio and started freeing up the music, and that was happening to a lot of bands. A lot of musicians were trying to get a looser format in the studio, where before it had all been tightly controlled by the record companies.

JB: Listening to that track, it sounds like you were playing a Fender. Do you remember what you used?

JC: No, I was playing the Guild modified bass. I think you see that same bass in the classic Woodstock photos. It was stolen and just got returned to me; it’s a great story. After about 48 years, it got returned. I’ve got it right now in my studio, and it’s in perfect shape. When that bass got stolen, I had one manufactured. I just added some electronics to it – this was the precursor to all of the Alembic stuff. At any case, that one is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

JB: I am so happy to hear you have that bass back in your possession.

JC: Yes, it’s a great instrument.

JB: Did Eddie Cramer [engineer] run your signal through the board combined with an amp to blend your sound on Voodoo Chile?

JC: No, it was very unorganized. Much to the chagrin of everybody, there was just a Fender Showman bass amp on the floor out there plugged in. It wasn’t structured, we weren’t all supposed to be there, so it happened as a jam to play, and then he threw everything up to record it as best he could. If he had his way, there would be a lot more isolation and better recording. Naturally, he’s an engineer and wants to get the best out of them. So there was a lot of leakage; we were receiving some feedback coming off one of the amps, too.

JB: Let’s talk about tone. I know that you’re a stickler for getting the right and I was wondering, was this a frame of mind that was in your thought process early on, or was it something that developed as you had opportunities to play with different musicians and bands?

JC: Well, early on, that is what entices you to listen to music in the first place – the touch and tone of any musician that they get on their instrument, whether it be a wind instrument, and you’re talking about Roland Kirk and Eric Dolphy, or George Van Eps and Jim Hall, if you’re talking on guitar. The tone is the seductive nature of music that pulls you into it. To me, it is much more seductive than the notes, themselves. You have your melody that pulls you in, but the tone of the individual player is what brings you into the personal world of music. Otherwise, you could listen to calliopes play, or mechanical pianos… The music, itself, and the composition and structure of the music, of course, is another aspect all together, but individual players pull you into that emotional personal aspect, and I think that is something that has always intrigued me. Ever since I started playing – and I tell this to my students when I teach at the Fur Peace Ranch out in southeast Ohio – if you develop good tone, it will lead you to your notes, and if you don’t develop good tone, it is going to sound bad to you, and how inspiring is that going to be?

JB: Not at all… I am a bass player, myself. For me, I used to play with a lot of horns and sometimes relied on using a pick to cut through the dense wall of sound.

JC: Yes, that’s correct. When I did my first recordings, they wanted me to use a pick on a record. There was a great musician, Carol Kaye, who used a pick and got a sound that was so clear from the electric bass guitar that was so different than a standup double bass. You had all the popular music going on in the early ‘60s, and most of it was done with standup bass players playing the electric bass guitar. You had guitar techniques start to come in and develop in the ‘50s when the Fender bass was developed. From a recording aspect, the engineers loved that, because you had the percussiveness from the pick that you often did not get with fingers. I enjoyed that, but what it made me do was develop my finger technique so that it would, as you say, “cut through the mix.” That is where your tone comes from. It’s really from your hands. It is not from the settings on your instrument. Hopefully, you want to give the engineer in the studio very little to play around with. You want to center it.

Now, one of the things that the Fender bass did that changed the recording industry so much was by placing that offset pickup that Fender developed in the center part, which speeds the length of the string. When you played the Fender bass, it had that space in the recording mix that was unique and almost always was able to be heard. So, you had people picking up this instrument for the first time that didn’t have any preconceptions. Later on, in 1960, when I started to play, the Jazz Bass came out, that was my first bass guitar. I wanted to go with the Jazz Bass because I liked the split pickups and more tonal aspects. I took that guitar and added the Precision pickup by the neck – right at the base of the neck – so if you look at the early pictures of Jefferson Airplane, you’ll see three pickups on that Jazz Bass. What I was able to do with that was put them all on concentric pots. You get a little of that standup bass sound up by the heel of the neck. I would then add in the clarity in the middle of the instrument with one of those Jazz pickups, getting the midrange, but at the same time getting that round low end. Then, I discovered the Guild instrument, which was a somewhat hollow-bodied instrument with a block down the center with a short-scaled neck. I really liked being able to chase the round tone of an f-holed instrument. So that pretty much is how I’ve gone most of my career; never solid bodies. I’ve taken a culmination of twenty years to develop with Epiphone the Jack Casady Bass, which is patterned off of Les Paul’s low-impedance instrument. By the way, all of those instruments have flipped over to low impedance. I was always chasing that rounder tone of acoustic or f-holed instruments, but I wanted the clarity of a solid-body, so that is pretty much what I think I achieved with the JC model that I have out there now these past twenty years.

JB: This summer will be the 20th anniversary of the Jack Casady Bass. Will there be any upgrades or enhancements made to the current model that you can share with us?

JC: Well, there is no need, because it’s just right, although it will have a different color. We just played the Fillmore, and Jim Rosenberg came up and did a good photo spread and video that will come out in the early summer. There is going to be a bunch of fun stuff to come with it, such as a special gig bag and strap, and a little passport folder that I just signed 600 copies of. We put out a really nice deep cherry red and striped maple top instrument that I took right out of the box, as a matter of fact. This is the prototype for the color that I okay’d and played at the Fillmore. There’s a bunch of stuff up on YouTube you can hear it yourself; it sounds fabulous!

JB: Let’s breakdown your live rig setup; what are you running through for amps and cabinets?

JC: Well, for my rig in the electric versions, I use an Aguilar 300-watt tube bottom and Aguilar 12-tube preamp top with 4x10s; an all-tube system. Then, in the acoustic version of Hot Tuna, I use a George Alessandro Basset Hound hi-fi top all-tube from point-to-point with an Aguilar twin 8” and 5” bottom that I helped develop with Dave Boonshoft. On the acoustic set up, I play a Tom Ribbecke Diana 1 model – a spec bass that Tom made for me three years ago in honor of my late wife, Diana. If you go on their website, you can see it has an all hand-crafted large body – he calls it a Halfling; half the top is flat, and half the top is arched, but it is a totally different development and a one-of-a-kind instrument. I have a Diana 2 out there, and you can see pictures of that when I play for the acoustic set up.

JB: Are you running dry, or is there an effects pedal chain in the signal path?

JC: I have used those things at different periods, like everybody, but I find that it draws away from the tone of my main instrument.

JB: Do you think it makes things sound muddy, sonically speaking?

JC: I don’t know if it is muddy, it just steps it back some. You can compensate for it, but I find it steps me back away from working with the tone of my fingers on the instrument; it pulls me away from the instrument. Effects are fun and all of that, and at different times, I have used them. What I use as an effect in my electric rig for sustain and growl is cranking the amp way up to distorted levels, rather than using a pedal button mimicking distortion. I use a Versatone amp that was developed by Bob Hall in the mid ‘60s that Carol Kaye was using in the studios. The Guilds and the Epiphones that I use now have a 35-watt bi-amp with two 7590’s on the low end, and two on the top end through a mono speaker. I used that to record the very first Hot Tuna acoustic album at the New Orleans house with my Guild modified instrument. When you turn it up at about 10 o’clock, it sounds just gorgeous, with sweet high fidelity. When you turn it up to about 12, it starts to sustain a bit, and when you turn it up beyond, you get that growl-distorted-sustain forever. I feed it through a pedal, and mic it separately, putting it through a PA system that blends out my general sound.

JB: Do you ever use in-ear monitors, or are you not into that side of technology?

JC: Yes, I have used them with Jorma when we’re using a bigger band and have more people on stage.

JB: So, it’s more for larger ensembles that you’ll use them?

JC: Yes, exactly.

JB: I wish to leave you with one last question, Jack. Was there a “light bulb” moment that made you realize you were destined to become a professional bass player?

JC: Yes, actually there was. I started working regularly in all of the clubs in a variety of bands in the DC circuit. One of the great musicians in the area was Danny Gatton, a good buddy of mine and a year younger than myself. We traded around in various bands playing from time to time. He called me up on one occasion and says, “Listen, I have a gig coming up for two weeks in a club six nights a week, and my bass player has gotten very ill. Do you know of any good bass players?” In those days, there was 40 on 20 off, five sets a night, no sets on Sunday, and there weren’t very many people that played electric bass. We’re talking 1960, and I’m 16 years old. He says, “Why don’t you do the gig,” and I say “Listen, I’ve never played bass before,” and the joke goes, “How hard can it be, it just has four strings?” [chuckle] Anyway, I borrowed his bass player’s Fender Precision for the gig and really fell in love with the tone and thought we may have something, here.

That year, Fender had come out with a Jazz Bass, and I think I ordered it from Levitz Music in northeast Washington. I started playing with it and playing along to records, and then my work quota increased dramatically, so to speak and I fell in love with the instrument and the tone and started developing a picking style on it using my first two fingers as I moved around on the instrument. There were guys in the jazz world such as “Monk” Montgomery, who was one of the first guys to play in that genre much to the chagrin of Downbeat magazine. It was sacrilegious, so to speak! In a lot of the country, bands and rockabilly bands started using a Fender bass, as well. So that is pretty much how I started getting into it. When I would meet up with Jorma from time to time in New York in the years before I moved out to California, I was listening to a lot of the folk music world players, and then when he went out to San Francisco to play on the folk circuit out there, he was approached to start a so-called “folk rock band.” He and I were talking and he had just joined the band and I told him that I was playing bass guitar on a consistent basis. He said, “Great, I’ll call you back.” Shortly after, he called back and asked if I would like to come out to California. I said sure, so I dropped out of school and went out west, full-time. The rest is history…

JB: Here you are today in 2017, still making music almost sixty years later! Thank you for talking the time out of your hectic touring schedule to sit down with me Jack. It’s been a complete honor.

JC: My pleasure, Joe, and make sure you come out and say “hello” when we come to Connecticut this summer.

“Living Colour’s Time’s Up 30 Year Anniversary”

“Living Colour’s Time’s Up 30 Year Anniversary”

Originally published in Bass Gear Magazine

Originally published in Bass Gear Magazine