“A Voice That Still Carries,

Yet Everything’s Different Now”

By Joe Burcaw

November 11, 2019

Originally Published in Bass Gear Magazine

It’s hard to believe it’s been over 30 years since the 13-year old version of myself first heard ‘Til Tuesday’s mega smash hit, Voices Carry, on MTV and terrestrial radio all across the United States. It was this single that the masses will forever remember them for releasing, yet the band had five singles reaching the U.S. Hot 100 charts during their short, but highly influential, tenure between 1985-88. Oddly enough, it was the B-side to Voices Carry that really caught my attention. Are You Serious was this dance/funk masterpiece filled with infectious hooks and catchy syncopated guitar and bass grooves, a la Nile Rodgers and Larry Graham. A true listening pleasure for those of us affected by groove.

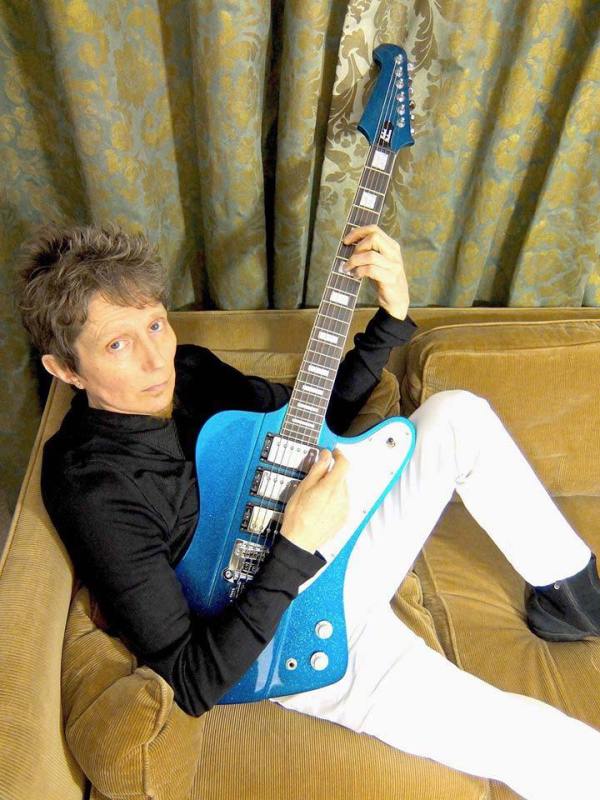

It was the stringed rhythm unit of Robert Holmes and Aimee Mann who inspired the musician inside of me to explore the true genius of ‘Til Tuesday’s catalogue, and ability to craft new wave pop gems that will forever remain lodged in our subconscious minds until the end of time. I am writing this piece not only as a huge fan of ‘Til Tuesday, but as a huge fan of Robert Holmes and his guitar prowess, which has unfortunately flown under the radar from the general public. My intention is to change that perspective, and to inform people of what this unsung guitar hero brought to the table as a founding member of Boston’s biggest export during the ‘80s. It was an absolute thrill and honor getting a chance to sit down with Robert to discuss everything music and beyond.

JOE: Hey Robert, thank you so much for taking the time out of your busy schedule to hangout and speak with me, we have a lot of things to discuss in a short amount of time. So, let’s get to it, mate!

Refresh my memory; you were born in the UK, but emigrated to the States (Boston area) when you were still a youngster, yes? What was the work opportunity that landed your family over the pond?

ROBERT: My father worked for the Christian Science Monitor and their headquarters were in Boston, so the whole family emigrated as permanent resident aliens in 1967.

JOE: Once you settled into American life, was it difficult assimilating being the new kid on the block? Was there always a yearning inside of your inner core that led you to the guitar, or to music in general as a child? Do you come from a musical family, or did your passion for music arise from somewhere else outside of the family dynamic?

ROBERT: Being English worked for me as a new kid on the block in America. I was always interested in music, my parents were both actors, and my father was in a long-running musical before he took the job with the Christian Science Monitor, so there were always show tunes in my childhood. But I was that 5 or 6-year old child who saw The Beatles on television and decided that was it for me. I wanted to play guitar since then.

JOE: That seems to be the general consensus for a lot of musicians who grew up during the heyday of Beatlemania. I missed that moment in time and sometimes imagine what it would have been like if I was born a decade earlier. Did you immediately [after seeing The Beatles on television] ask your parents to purchase a guitar, or was it a few years later you decided to pick it up? Were there any individuals, such as music teachers or neighborhood friends, who helped influence your life pursuit of music beyond shredding in the bedroom for hours on end?

ROBERT: I think I wanted to play guitar immediately and they got me a ukulele first when I was 7. I got a guitar after we moved to America – about age 11 – and although there were neighborhood and school people I was aware of who played instruments and a handful of times I got together with others to play, it wasn’t until I joined a band and got an electric guitar that things started to move forward, at age 13. Before that, it was mostly figuring out records by ear and lots of sheet music songbooks with guitar chords. I had quite a few of those, and I also bought sheet music for individual songs I wanted; hits of the day from bands like T Rex and The Sweet.

JOE: Tell me about this point in time once you started the band at age 13. What was the impetus that pushed you into joining the band? Was it school friends conspiring together to rule the world, or just the need to be part of something creative and self-exploratory?

ROBERT: My oldest sister, who is 4 years older than me, had a boyfriend in her senior year of high school, and he heard me playing in my bedroom when he was over visiting her. He played a little, and his brother was a keyboardist in a band that was looking to replace their guitarist. He mentioned me to his brother’s band and they decided it would be a cool gimmick to have a young boy who was English as a guitarist. They were all 17 and 18 years old. Ultimately, I wanted to be in a band, and so when they asked me, it was a dream come true, and there was no hesitation. They would advertise gigs as featuring a 13-year old guitarist child prodigy from London. The band leader had a distinct flair for promotion, as I was definitely not a prodigy, and not exactly from London, either. I was in that band for the next ten years.

JOE: This was the same band you were performing with up until the ‘Til Tuesday gig came together, yes? I can only assume, it must have been liberating being so young playing out at the local pubs and functions all around the area in front of an older crowd? Would you say this experience really shaped your desire to push forward as a professional musician once you were of proper age? Were there certain key aspects of being around these older band mates/musicians that made you either want to practice more, or want to learn the fundamentals of proper musicianship when it came to entertainment?

ROBERT: Yes we started ‘Til Tuesday six months after I left that band. It was liberating and gave me a little secret life over the others at my high school. I was even given special leeway where I didn’t have to start my classes as early as my other classmates, due to a provision in the MA state law that said something along the lines of a student with special requirements that relate to their ultimate career choice must be catered to. The leader of the band (the one with the flair for marketing) discovering this provision, made a pitch to my high school, with my parents’ blessing, that I was such a child and I might need to catch up on my sleep, as a result of being out performing in clubs the night before. So, for my last year in high school, I started at 10:10 am and wound up graduating early in January.

That band was very driven and quite professional in its general attitude and approach, so it really raised my game. The leader was very much in charge, and routine bad habits so many musicians seem to have – like being late, or noodling, or just having a sour attitude, etc. – never went by unchecked. It wasn’t, however, a band with a premium on good musicianship. The music mattered, of course, but the main goal was to write hit songs and get signed by a major label. Ultimately, along with other issues, the lack of focus on actually becoming better musicians led to my dissatisfaction and departure.

JOE: Regardless of whether or not the band had focus on becoming better musicians, what an amazing lifestyle you must have led getting to sleep in late, and graduating early, all in the name of “catering to your career.” Also, it seems like your parents were extremely open-minded individuals, allowing you to pursue this life path at such an early age in life. Your relationship with them (back then) must have been built on a lot of trust, and a true understanding of your musical and artistic needs, yes?

ROBERT: Both my parents were actors originally; my father giving it up only when it became obvious he wasn’t making enough money to raise a family. So they both were very supportive. Also, I was on the case pretty early, so they could see I was serious. I graduated early only because I found out it was possible, so I applied myself to school work seriously for the first time. It was only for my last year in high school that I got to show up late. The leader in the band who was so serious actually came over and tutored me in math when I was having difficulty. His drive had as much to do with me getting an easier ride at school as anything my parents did. My parents were impressed with him, so it all helped. He didn’t do drugs or even drink at the time, and was quite a scholar, himself.

JOE: Let’s fast-forward to the moment you split from your childhood band to meeting Aimee Mann at a mutual friend’s house party in Boston. Walk us through the sequence of events, if you could, please.

ROBERT: I had left the band I was in for ten years and was chomping at the bit to get involved in a new band. I went to a few auditions and poured over the want ads and was actually planning on moving to England, thinking my prospects might be better; reasoning it worked for Jimi Hendrix! I had even sent a letter to The Pretenders after James Honeyman Scott died.

I was in touch with some friends from school. One in particular, Steven Freddette, was a guitarist in a band called Scruffy the Cat, who after some personnel changes went on to some measure of attention and success. Steven casually invited me to a party at his apartment in the Fenway area of Boston. I was living in Hingham, but took public transportation up to go this party with the specific goal in mind that I might be able to meet musicians, since he was one, as were his roommates, and so there would more than likely be others.

I was right, and Aimee was there. She was living a block away at the time with Michael Hausman, who wasn’t at the party. I recognized her as the bass player and singer from her band The Young Snakes, whom I had seen opening up for someone. Also she had dated, very briefly, a guy who was the singer in my first band for the first five years, so we had him in common. That singer, Jace Wilson, was now the singer in the band Michael Hausman played percussion in.

I was pretty aggressive and friendly and told her right off the bat I was a guitarist and I was looking to get into a funky dance music type band, which is where I was at the time. She told me she had some studio time owed her and that she wanted to put together a band for a recording project, only, and that she was looking for people, too. She also said she was into funky dance music and complained that The Young Snakes were too deliberately artsy and non-commercial. So we exchanged phone numbers and connected about a week later.

JOE: It must have been a bit of relief connecting with Aimee and putting the wheels in motion to start up another project with some potentiality? What was it about her that made you become so bold and up front about your intentions of starting up a funky dance band? I know this is a cliche adjective, but people use the word “energy” when describing a chance meeting with someone possessing stature and allure. Did she reel you in with that type of vibe? We need to be up front and honest here, she was and still is all these years later easy on the eyes.

ROBERT: Absolutely. I was thrilled to be starting to work on music with someone serious about it. I was definitely attracted to her, being an attractive woman, and was delighted by the idea she would be fronting the band. Although she had said initially she was interested in a recording project, I had little doubt we’d eventually be starting a band together. I had thought before meeting her the best candidate for me to start something with would be a bass player; a lead-singing bass player even better. An attractive woman lead-singing bass player was like hitting the jackpot. I was bold and upfront for all those reasons. I certainly didn’t know anything about her ability to write at that point, and I don’t think it even occurred to me.

JOE: Okay, so you two exchange numbers and make plans to speak on the phone at a later time. Was Aimee as serious as she seemed to be at the party, did she call you about getting together to record at the studio where time was booked, or was it more of you chasing her down? Tell me about how the two of you were able to reach common ground feeling each other out, musically. Chemistry is so vitally important when it comes to working with other musicians. Was it an easy transition or did it take some time getting comfortable with each other as writing partners?

ROBERT: Well, I felt like she should have called the Monday following the party, but it took her at least a week to connect with me. We arranged to meet at Darkworld in Watertown to play through some song ideas. This was an apartment where several members of The Dark lived and where they rehearsed in the kitchen. Hausman was on drum kit, we had the keyboardist for The Dark, Bob Familiar, Aimee on bass and me on guitar. We very quickly came up with about three or four ideas. Aimee had the bones of Are You Serious, and that so was the very first thing we did, followed by No More Crying, and then I forget exactly what else. I think a song called She Said that never made it.

I think we got together one other time with that band prior to recording, and by then Aimee and I had started getting together regularly at her and Michael’s apartment in the Fenway. Aimee and I got along really well and we wrote loads of songs. At least one or two each time we met, and we recorded versions of them on cassette. I kept my musical cards pretty close to my chest and just offered up ideas I thought she’d like. We came from very different worlds. I had all this classic rock background and she had none of it, and didn’t like most of it. She was pretty new to music, compared to me. She didn’t really like free-form guitar solos; she didn’t much like distortion. She also didn’t like effects like wah wah, at all. She said she thought Steely Dan sounded like “a bunch of guys with long hair sitting around smoking pot.” So rather than argue or confront or defend any of this, I just kept quiet and only offered up ideas within the parameters she seemed to like. I wasn’t an artist with a defined vision, I was more an all-purpose rock guitar player looking to adapt and do whatever it took to get or create a gig. I also was in the habit from my previous, and only band, of actively writing songs, so I let that be the focus, above all. I just sort of agreed when talking about the importance of simple lines supporting the song etc., rather than flashy guitar parts. I mean, I loved flashy guitar parts, but I didn’t mind being a lot more subdued, if it meant fitting in with what we had going on. Aimee was very quick, writing lyrics down on the fly etc., and took the reins quite happily when we were writing, and really I was fine with it. I think often in musical partnerships, there will be one person who is more or less leading. It’s quite hard for two people to be equally inspired and writing a song together simultaneously. I’ve always been good at being a sounding board, gentle opinion, human looper-type assistant in a songwriting session, and that was my role with Aimee, most of the time.

JOE: I always felt you and Aimee were the driving force behind the band’s success, without knowing a single thing about the band’s professional working dynamic. It was that “energy” thing that can be felt, even from pictures, as odd as that may sound. As you said, you took on the role of being more of the silent agreeable personality, allowing Aimee to run with her vision. Tell us about getting Hausman involved, and how that all fell into place? Was it purely he being the closest drummer within arm’s reach, since he lived with Aimee, or did he play in a particular way that made him stand out from other drummers on the scene? Did Michael possess something unique that could enhance ‘Til Tuesday’s sound?

ROBERT: Michael was completely willing to play like a drum machine and keep it really simple and serve up the songs. Being Aimee’s boyfriend made it very convenient, but he was a solid guy, all around. Definitely a good guy to have in a band. I don’t remember much detail about him officially joining, but I think Aimee more or less announced he’d be joining us full time and quitting The Dark. We certainly never auditioned or even talked to anyone else. Honestly, at the time, my feeling about him musically was that he was more of a blank than a positive or a negative. He wasn’t like a guy you’d love to jam with, but he’d do things like keep good track of tempos and gamely cover his drums with towels if it was a tiny loud room. In retrospect, he came up with the little hooky snare skip on Voices Carry, so I think that definitely makes him a positive.

JOE: That fill before the middle eight keyboard solo in Voices Carry is pretty hip, too. I get what you’re saying regarding his playing. He’s no Vinnie Colaiuta performing Zappa’s The Black Page while simultaneously eating sushi, but he had a rock-solid backbeat that never got in the way of the other instruments. His live feel seemed to diminish with each album as the drum programing trend began to dictate that quintessential sound of the ‘80s.

ROBERT: Yes there were fewer and fewer recording sessions where we started with a live recording of the band. The whole first album was done that way, but only a handful of tracks on the last one were. I think much of that had to do with songs not being completely written by the time we started recording them.

JOE: Once Michael got on board, did the three of you begin rehearsing/writing together without a keyboardist, and then after some time decided you needed to fatten the sound a bit sonically? How did Joey Pesce [keys] end up joining the band?

ROBERT: We always wanted keyboards. I don’t remember if Joey came on before Michael, but I think maybe he did. I think maybe we found Joey as the second keyboard player we even talked to, and then very shortly after Michael joined, officially. Aimee knew of Joey from Berklee, and I think she might have run into him when she was there putting up an ad on a musicians wanted bulletin board. We met up and he was great. Fantastic little parts with interesting sounds just flowed out of him. He was calling himself a bass player at the time, and so during our first few months of being a band, Joey was borrowing a little keyboard from his roommate. It didn’t take long before we had the full line up and we were rehearsing regularly and always writing songs at those rehearsals. We did our first gig very quickly and then just kept rolling on as a local band, from that point. I never have been in a band, before or since, where everything was so easy. Things just dropped into place very quickly.

JOE: Yes, it does seem that way. When things gel quickly, it sometimes propels the ship into the abyss of good fortune. The timeline from the band’s inception to getting signed by Epic records was from 1982-84? Where were your “go to” spots to perform at around the metro Boston area, and did you make it down to Providence at some point?

ROBERT: March 18th, 1983, was the first gig. We won the WBCN Rock n Roll Rumble, had management, and were talking to record labels all within the first twelve months. We played every Tuesday at The Rat for a month and played in regular rotation at The Rat, Storyville, Jumpin Jack Flash, Jonathan Swifts, Spit (next door was called Metro which is where we won the WBCN Rock n’ Roll Rumble), The Channel, JC Grovers in Beverly, Jacks in Cambridge, The Inn-Square Men’s Bar, and The Casbah in Manchester, New Hampshire. We played in Providence, too. We opened for Billy Idol at The Living Room, and we played Captain Morgans at least once.

JOE: Tell me about that BCN Rock n Roll Rumble; was it true you guys beat out The Del Fuegos to win the competition? How did it work, a bunch of local bands with a buzz were selected by talent scouts to compete for management and a record deal? Were you guys allowed to choose from specific record labels, or was it more of the label head corporate guys appointing who they felt fit to represent the band? I sense a lot of vultures popped out of the woodwork offering you their services once it was declared ‘Til Tuesday were the winners, no?

ROBERT: The Rumble was organized by WBCN, the local FM radio station. I think you had to have music played on the local show to qualify. The winners got things like recording time, percentage off at local music store, free haircuts at a local hairdressers, free ad space in local music paper, photo shoot, etc., and of course an amount of local press. There was no management or record label involved as part of the prizes. Sometimes, one of the judges would be an A&R person, but it was basically a souped-up battle of the bands. I remember we didn’t have enough material for two sets, so we repeated songs. We beat The Sex Execs in the finals. We might have beaten The Del Fuegos in an earlier round. It went something like four bands a night for a week, winners go up against winners until a final two go up against each other at the finals.

I’m not sure how much of an impact it had on our ability to get a major record deal, but it certainly helped us to become favorites at the radio station and they really got behind us. When we got signed, we signed our record deal live on the air and they played us relentlessly before and after the record came out. I can’t think of any other Rumble winners that went on to get record deals. I think there was even a “Rumble curse” rumored because many winning bands over the years went on to nothing, or just broke up shortly after.

JOE: How soon after the Rumble did you get signed, and was it a bidding war that came down to Epic records throwing on the table the best deal? Mike Thorne the producer got involved with the first record; whose choice was it to appoint him?

ROBERT: We got turned down by most of them, first time around. I think it was a few months after the Rumble. There was no bidding war. I forget exactly what the chain of events was that led to our signing, but they were watching and monitoring us. We went into the studio and cut one or two tracks with a producer they had on staff, John Boylan, prior to signing basically to make sure we could cut it and that Aimee could sing. John Boylan was a pretty big name and was involved in a vaguely similar liaison type role between the band Boston when they signed to Epic. I think he was probably on the short list to produce our first record, but I don’t remember why it didn’t happen. We talked to quite a few producers, some suggested by us, some suggested by the label and met with a few of them. Mike Thorne was one of them I think the label suggested, and we liked him the best, basically.

JOE: Mike Thorne was quoted saying back in 1999, “‘Til Tuesday were very easy to work with and very competent and able to adjust fluidly if a new more interesting musical direction was spotted. Aimee in particular wasn’t afraid to speak her mind and was very determined, such as when she needed to learn on bass the synth line to Love in a Vacuum.” Would you agree with Mike’s assessment?

ROBERT: I suppose so. I don’t doubt we were easy to work with. Aimee was definitely not afraid to speak her mind, but I remember working on one track later with Rhett Davies and Aimee being sort of annoyed that he wasn’t 100% happy with her bass performance on a song. I remember her sort of pleading in an exasperated way, “That’s not good enough?” He ended up getting Marcus Miller to play it. So I supposed up against some bands, we might have seemed like we knew what we were doing as musicians, but I know there was a level of musicianship that we most definitely weren’t on.

JOE: The band decides on Mike Thorne, and then regrouped shortly afterwards down in New York City to commence recording, yes? Do you remember how many songs you had prepared, and were there any revisions made to existing tracks or tracks not used on the final pressing still locked in Epic’s vaults? How about gear, any recollection of what guitars, effects and amps you used during tracking?

ROBERT: We had pre-production rehearsals with Mike Thorne in Boston at our rehearsal space for about a week or so. I don’t remember if there were tracks we started recording that didn’t make it on the record, but I think not. I purchased a Marshall JCM 800 half stack with the recording budget, and I’m pretty sure Joey got at least one new keyboard, but otherwise we used what we had for gear, originally. I don’t think I even had a spare guitar. I used a Strat I joined the band with, and I only had a few pedals: a chorus (probably a Boss CE2), a Boss overdrive (the yellow one), and I had a DOD rack-mountable delay. I played through the Marshall and a Roland JC 120 (which was my only amp before the Marshall) simultaneously as part of my regular rig. I don’t quite remember how I split the signal, but I remember describing my set up to the engineer on the record, Dominic Maita, and him saying “I see, going for a big guitar sound, eh?” Mike Thorne brought some extra guitars. I remember a Les Paul, but I don’t clearly remember using them, except for maybe the odd double.

JOE: Should I assume the band was ultra-tight from two years of gigging under your belts? Was it a smooth transition getting into the studio atmosphere and nailing the takes, or were there learning curves as a result of the band’s limited recording experience? Did you personally feel challenged being “under the gun” getting your guitar parts perfected with one or two passes per song? Which brings me to your tasty and melodic solo for Don’t Watch Me Bleed. It’s really the only true guitar solo on the entire album; why is that? I always felt that Robert Smith mimicked your tone and phrasing sensibility on The Cure tracks like Fascination Street or Open; it’s not a deliberate cop, but interesting to hear some stylistic similarities.

ROBERT: We were tight, but there were a few changes made to some songs that made them newer for us. I Could Get Used to This was completely different. Mike Thorne had made sensible suggestions about many things, one of them was the lick I played in Don’t Watch Me Bleed. The way the intro of the song goes with the guitar lick at the top of it is what I used to play during the chorus, and he had me change it so that it was more of an answer line, because otherwise, it occurred at the same time as the lead vocal. His idea was “so don’t just kiss me goodbye,” then the lick. Seems obvious to me now, not to have the line occur simultaneously, but at the time, it was a sort of defining example of why you need a producer. The solo was a written sort of solo, as there were really no freeform moments, musically, in ‘Til Tuesday, ever. It was always scripted out.

Aimee really didn’t like much ornamentation. She was, at the time, the type of artist who finds things like vibrato overly expressive. I went into that band and album with the feeling that I was going to completely sublimate my ego and just serve up the songs. It was not my instinct to do that, coming from classic rock, I actually like guitars to express themselves more freely, but in ‘Til Tuesday, the main challenge for me, personally, was to pull back. I was super careful when we recorded all the basics, to play tight and clean and unornamented. I imagined at some point we were going to address the guitars, and then I would have a chance to push and pull a little, but it never happened. The guitar track for Voices Carry, for example, was the track I played on the basics with the keeper drum performance. There was no later. I don’t remember how much time we spent recording, but it seemed pretty quick. Boom-bang-boom, we were mixing. I’m not very familiar with The Cure’s Disintegration album, but I would be flabbergasted if it was somehow revealed Robert Smith was aping Robert Holmes.

JOE: I know it sounds cliche, but it’s those moments of tension and restraint that usually result in ways not originally intended. I found from day one of listening to your guitar parts they served the songs perfectly. There was no interference by adding blistering 16-bar shred like solos, just to fill space. A point needed to be made resulting in an album with only one solo and multitudes of hip riffs and rhythmic/sonic embellishments that were memorable and hummable. In my opinion, that’s pretty damn cool, and extremely noble, considering you could have gone down the other route of not being a team player. Looking back in hindsight, would you have addressed the basics and try swaying Mike Thorne and the band into letting you cut loose a little more with some slight improvisational lead playing?

ROBERT: I think in general, ‘Til Tuesday could have been a little looser and easier in their playing, and I think it could have been done without sounding like it was gratuitous riffing or too much of something. But we might have had to become slightly better players, first. It was very much my feeling when the first album came out that we sounded, or more specifically I sounded, overly cautious and polite, but looking back, I find it hard to care about it, now. I’m sure I’d be much happier with the results if we were able to make those records now, because I’ve had 30 plus years more experience. But even now, if I found myself working with the same people in the same situation, I’d more than likely do a similar thing and just play it safe. It’s more of my nature to be chameleonic. Some people don’t know what they like or don’t like until they hear it, others really know what they like and don’t like. You couldn’t sneak musical parts past the Aimee of the ‘80s. If everyone loved something, she might be persuaded, but in general, she knew what she liked and didn’t like. It’s a different atmosphere making music with people who absolutely love guitar, versus making music with people who mainly see guitar as a means to getting a song and a point of view across.

JOE: I would like to conclude the first part of our interview with one question. What are you most proud of when listening back to the Voices Carry album? Was it the success of the title track, or are there specific guitar parts in songs that make you really appreciate your accomplishments?

ROBERT: I haven’t listened back to that album in its entirety for a very long time, and frankly I would find it kind of hard work, but I’m proud and glad it was successful, and I suppose it has its charms. There are live ‘Til Tuesday shows I’ve seen on YouTube I feel more proud of in terms of things like guitar parts in songs and our general band sound. I feel like that vibe wasn’t really captured on the record, but in general I’m just happy that people like any of it.